Jim Nuffield

Writer — Engineer — Dreamer

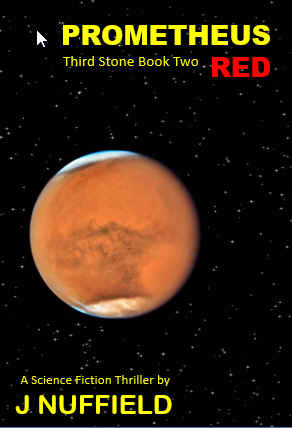

Prometheus Red — An Excerpt

Fisher Peak, Near Fort Steele, British Columbia – October 1, 2030; 11:30 PM

The snowy slopes of the Kootenay mountain range of south-eastern British Columbia sparkled in the radiance of a quarter moon. The distant light of the little mountain community of Fernie, nearly due west, lit the way through the Lizard Range Trench corridor, lending a faint, warm glow to the dense forest of jagged peaks. At 9,107 feet, snow was already beginning to accumulate. The minus-ten-degree air was crisp and clear and utterly calm. A few hundred meters below the site, scree-covered slopes topped the thinning tree line, exposing a ruined landscape of pulverized rock, scattered fields of fresh white snow and the odd stubborn little scrub of flora.

Fisher Peak was a regional landmark and a favorite hiking destination for locals and tourists alike. The last hikers, seeking to join the one-in-a-million signers of the log book at the top of the mountain, had long since departed. The season for that adventure was now closed.

Many decades ago, a silver mine at high elevation produced enough metal to bring prosperity to the Kootenay Mountain Region, supplemented by moderately successful gold panning from the Wildhorse Creek in nearby Fort Steele. But now, the area was deserted.

The site for the compound had been chosen for its elevation and relatively proximate location to the VAST Launch Complex in the Okanagan Valley. Several oddly shaped structures had been recently installed just out of site of the Fisher Peak trailhead, tucked behind a jutting outcrop of ragged granite overlooking tiny Nicols Lake, whose cobalt-blue waters were just beginning to surface harden with freshly formed ice crystals glittering in the moonlight, signaling an early start to the long winter deep freeze.

A four-meter-high, galvanized steel fence protected the compound from curious hikers and resentful protectors of the natural mountain environment. Each structure within was secured with heavy steel doors and locks, supplemented by a solar-powered security monitoring system. Scarlett and yellow signs screaming “DANGER – High Voltage” projected little doubt of the risks of attempting a penetration of the compound perimeter. The entire set of structures and equipment, airlifted to the site by Sikorsky helicopter only weeks ago, had been assembled in the space of three days. Even so, crudely wired to the gate was a plastic envelope containing a hand-written petition from the local mountaineering community. The signers implored the perpetrators of the ugly, polluting interloper of their alpine paradise to leave, and to take their monstrosities with them. They would get their wish well before the end of the winter, assuming the planned test was successful.

The primary structure was a basic, prefabricated concrete hut, formed in the shape of a cube, about eight meters per side. Atop the cube sat a four-meter-high steel hemispherical top. The circular base of the top sat on small steel wheels mounted on curved trucks resting on a circular rail. Cut into the round top, from base to crown, was a half-meter-wide rectangular slit. The hut resembled an astronomical observatory, but its purpose was much less passive.

A few meters from the primary hut was a secondary steel building. Its siding consisted of large metal vanes on pivots, the opening and closing of which were interlocked with a transfer switch controlling the one-megawatt-per-hour flow of electricity from the four lead-acid battery strings within. Still further off was the steel building containing the Uninterrupted Power Supply cabinet array, fed by two 2.5 megawatt generators, one primary, one standby, both currently standing silent. The UPS rectified the alternating current of the generators, charging the battery strings to provide pure, clean DC power to the capacitors.

For a successful test, the air had to be absolutely clear. This need had dominated the site selection criteria. Tonight, the Milky Way slashed across the apex of the sky, bright and clear and shining. Faint traces of pink and blue Aurora Borealis danced in the icy northern sky. The night was perfect.

In response to a remote command from VAST Headquarters in Kelowna, British Columbia, parts of the compound began to hum, breaking the absolute silence of the night. The dome on top of the hut began to rotate towards the southern sky and the roof slit opened, revealing a three-meter-long solid metallic tube within. A small receiving dish near the hut woke up and rotated to a position pointing high in the night sky.

1,532,000 kilometers out to space at Lagrange Point L2, a ten gigahertz solar-powered microwave pulse generator lit up aboard the VAST Ares-One satellite, sending targeted bursts of signal energy towards south-eastern British Columbia. At Fisher Peak, the receiving dish captured the signal and transmitted precise coordinates to the targeting computers a few hundred kilometers away in Kelowna. The computers then aimed the tube beneath the dome in a series of successively smaller fine-tuning adjustments. Less than four minutes later, the deuterium-fluoride infrared chemical laser was locked into position. A final pulse completed the handshake between the ground based laser and Ares-One.

In Kelowna, VAST control center operations Chief Engineer Sandy James nodded his assent. The generators fired up and began to feed the rectifiers. Twenty-five seconds later, instrumentation displayed a perfectly straight-line DC power curve. All systems were green and ready for the test. James took a deep breath.

This is an expensive one, Sandy. Don’t fuck it up.

Upon James’ approval, the Fisher Peak laser lit up, its one megawatt beam piercing the clear night sky. Eight and one quarter seconds later, the full brunt of the laser, its power ablated to 820 kilowatts by the atmosphere remaining above it, found the dead center of its target.

At Lagrange 2, a small dish mounted on Ares-One received the concentrated power from the earth-based laser. Four minutes and twenty-three seconds later, its sixty kilowatt-hour battery bank was fully charged. This was part one of the test: a remote charge of a battery system via earth laser.

OK, now the big one, James thought. He was always nervous about prototype testing. They had tested it hundreds of times in the lab at this power level. But they had not tested it over a distance of 1.5 million kilometers through earth’s atmosphere. Only a live test could do that.

Powered by the newly charged batteries, the solar-sail array began to deploy, bypassing the solar-paneled backup system. Opening in the silent vacuum of space, the sail exposed its two thousand square meters of surface area at precise right angles to the mountaintop compound at Fisher Peak.

The Ares-One satellite would employ no thruster engines or fuel, yet if VAST engineers got it right, this would be the most revolutionary space craft in the history of flight.

“Initiate flight configuration,” James said aloud. At the Fisher Peak hut, the deuterium-fluoride laser startup sequence began. A casual observer would not see the beam of coherent light in the clear night sky, but the electric hum of the capacitors hinted at the level of power being delivered to the satellite.

As the invisible beam struck the Ares-One sail, the effect on the satellite was immediate. A resulting energy imbalance destabilized the position of the satellite, like wind on a canvas sail, delivering a thrust of 100 newtons on the 1,000 kilogram space craft. The thrust was tiny compared to the nearly 30 mega-newtons of VAST’s most powerful rockets, but for this test, it was enough. In accordance with Newton’s Third Law, Ares-One began to accelerate away from the energy source and out of the Lagrange point. The acceleration from the Earth and the Sun was modest, about one percent of the force of Earth’s gravity, or one tenth of one meter (about four inches) per second squared. But the constant acceleration compounded the satellite velocity with time. By the end of this evening’s preliminary four hour test segment, Ares would be more than ten thousand kilometers from the L2 point, running away from its energy source at 1,440 meters per second, ready for its second round of laser fuel. During each subsequent round of tests, the Fisher Peak laser would operate for four hours each 24 hour period, weather dependent.

Laser are comprised of highly-coherent, narrow beams of light. The most tightly focused lasers yet invented transmit at the size of a pencil point, spreading to merely the size of a pea at the surface of the moon. At LaGrange 2, four times further than the moon, the beam lit up a little over a square centimeter of the giant sail. This impact site would grow with distance as the satellite-turned-space-craft accelerated out of the solar system. Eventually, after achieving great distances measured in light-years, the diameter of the laser beam would spread to greater than the size of the sails and the energy imparted to the space craft would begin to reduce. Successive generations of lasers would provide even tighter focus and greater power, extending the range and acceleration of the system exponentially.

Assuming VAST engineers could hit 100% of its target for all time, the Ares-One space craft would theoretically reach light speed in 95 years of laser impact time.

* * *

There are more details on both Prometheus Red and its prequel, Prometheus Blue on my Books Page. Have a look!

If you like what you see here, please leave me some comments and let me know. I’m seeking representation to get Prometheus Blue and Red published and your comments will really help!!!

Writing My First Book

Writing My First Book My first book Prometheus Blue now complete and ready for submission, with book two Prometheus Red in final draft form. Now it’s time to embark on the journey to getting published. Just remember, I’m not an expert on this. As I described in an...

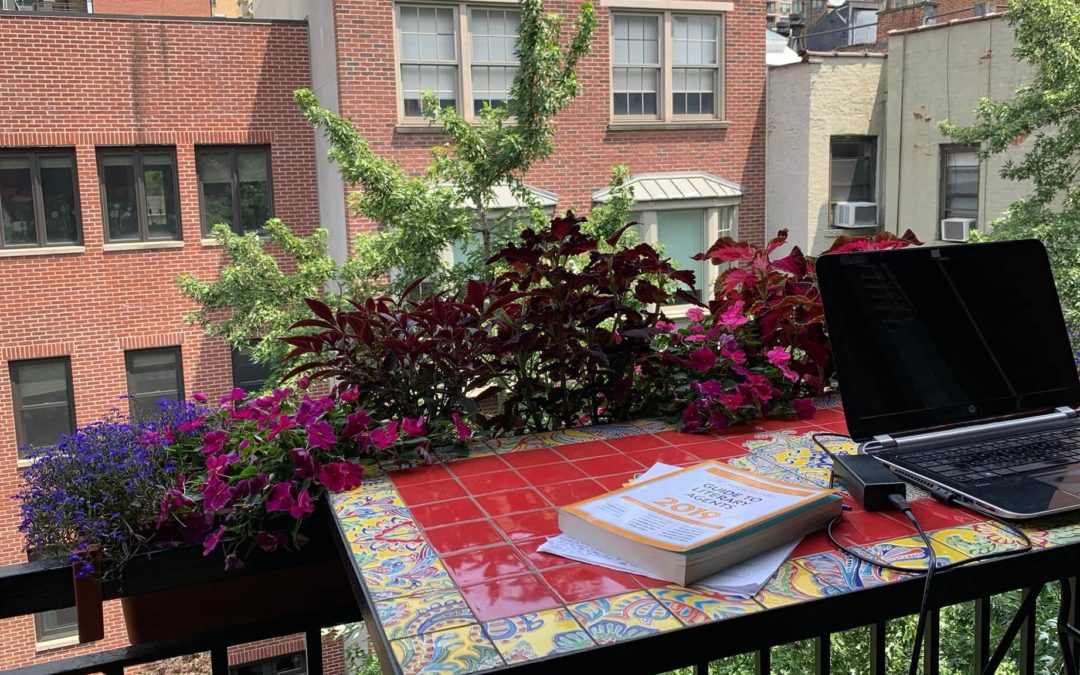

The Exoplanet Search

Exoplanet Search As we learned in Prometheus Blue, the Earth is doomed to the fate of a rogue star and as I have proven, there’s no way to stop it. Our only option is to get out of Dodge. We’ve got to accelerate the exoplanet search, find a new Earth and evacuate our...

An Aspiring Author’s Journey

An Aspiring Author's Journey Many years ago, I decided that I wanted to write. As an aspiring author and a lover of live theater, I authored a play – my first work of any real length. It took place in Vietnam during the fall of Saigon, in the final moments of the war....

Could We Blow Up a Star?

Could We Blow Up a Star? In my debut science fiction thriller Prometheus Blue in the year 2025 the world learns that a Sun-sized star fragment, 6 light-years distant, is heading directly for our Sun at 2,574 kilometers a second. It will destroy the Solar System and...

Is This Finally Our Planet Killer?

Is This A Planet Killer? As I mentioned in my last Initial Blog entry, my Science Fiction Thriller, Prometheus Blue – Book One of the Third Stone Series – is about Humanity’s response to the knowledge that the Sun and all her inner planets will be obliterated in 700...

Seeking Agent Representation

Late Summer / Early Fall 2021, I will be embarking on my quest for agent representation for Making Diamonds -- My debut psychological crime thriller, set in present-day Manhattan. Soon after will I will release my debut near future thriller -- Prometheus Blue, the beginning of an 800-year series about the end of the world. Prometheus Red will emerge hot on Blue's heels.